Dictation has shaped how I use technology for the past decade, but something shifted this year. A wave of new AI dictation apps came to prominence in 2025, each promising accuracy, speed and intelligence far beyond the built-in tools many disabled people depend on. Naturally, I wanted to see whether these claims held up — and how they compared to Apple’s Voice Control and Microsoft’s Voice Access.

It didn’t take long to see the divide.

Built-in dictation: the same old limitations

If you rely on voice to use your computer, built-in dictation is supposed to be the safety net. Apple has Voice Control and keyboard dictation; Microsoft has Voice Access; iOS, Android and the Pixel line offer their own mobile equivalents. They are always there, theoretically ready to work anywhere you place your cursor.

But accuracy remains their weakest point. Words are regularly mistaken, punctuation behaves unpredictably, and proper nouns often vanish into guesswork. Flows of thought become run-on sentences that need heavy editing — which is not exactly helpful for anyone, but especially not for disabled people who cannot easily correct mistakes.

This stands in stark contrast to modern AI dictation, which consistently produces cleaner, more structured text with far fewer corrections.

Formatting is another persistent issue. Lists, headings, email structure — all of it becomes manual labour again. And despite years of feedback, these systems still lack any meaningful contextual understanding. Every hesitation, every false start, every filler word appears on the screen exactly as spoken.

For navigation, Voice Control and Voice Access have strengths. They can move a cursor. They can press buttons. They can switch windows. They can keep you hands-free. But their dictation engines simply haven’t kept pace with how people write — or how AI now understands language.

A disappointing year for Apple’s Voice Control

This year has been particularly rocky for Apple’s accessibility stack. macOS 26 and iOS 26 have both been plagued by Voice Control bugs, some of which Apple has openly acknowledged. A handful were addressed in macOS 26.1, but several remain, and I’ve heard from long-term disabled users that these issues still interrupt their daily workflows.

More worrying is that accuracy appears to have slipped. Several experienced Voice Control users — and I count myself among them — have noticed that dictation quality in macOS 26 and iOS 26 is noticeably worse than it was in iOS 18. Given how central these tools are to independence, it’s disappointing to see regression rather than progress, especially in a year when external AI dictation took such a leap forward.

The result is a strange compromise: the tools that navigate can’t write, and the tools that write can’t navigate.

A year with Willow, Wispr Flow and Aqua Voice

This was the backdrop as I began exploring the new generation of AI dictation apps. I tested three in particular throughout 2025 — Willow, Wispr Flow and Aqua Voice — each representing a different point along the emerging landscape of AI-augmented speech input.

Willow and Wispr Flow offered the first glimpse of what modern transcription could feel like: fast, near-instant output with far higher accuracy than I’d seen from any built-in system. They cleaned filler words, corrected false starts, adapted to natural phrasing, and delivered text that actually resembled how I write. It felt as though a decade-long bottleneck had suddenly disappeared.

Aqua Voice took things further. It didn’t just transcribe accurately; it understood structure. Lists formatted automatically. Replacements and templates saved endless repetition. Casual chat flowed with proper casing and punctuation. Names were recognised and remembered. It became quick, reliable and — crucially — predictable enough to use every day.

These apps rely on cloud-based AI rather than on-device models, yet they still manage to deliver near real-time transcription and writing-level accuracy — which undercuts one of the longstanding arguments used to justify the slow pace of improvement in OS-level dictation. They show that high-quality, context-aware speech processing is not only possible but practical today.

In short, these AI tools showed what happens when dictation moves beyond transcription into something more like language understanding. They turned voice into a genuinely productive input method rather than a compromise.

But they all shared the same missing piece.

None of them can navigate a computer.

You can dictate beautifully into a text box, but you cannot tell these AI apps to click a button, send a message, open Mail, send an attachment, scroll a webpage or save a document. They write extraordinarily well, but they do not control.

Which brings me to the most unusual workflow I’ve used this year.

Living in a patchwork world

To get anything resembling a complete hands-free experience, I now combine two entirely different systems:

• AI dictation for writing

• Voice Control for navigating

It’s crude, but it works.

Aqua Voice handles paragraphs, emails and long-form writing with an elegance I simply never had before. But when I need to paste something, select text, switch apps or click a button, I fall back on Voice Control.

The writing feels as if it belongs in 2025; the navigation feels as if it was designed for 2015.

The contrast is jarring. The mental overhead is high. But compared with relying solely on built-in dictation, the patchwork solution is still a huge improvement.

This improvisation also highlights something crucial: independence shouldn’t require this much invention. We shouldn’t have to stitch together tools from two different eras to get one functional workflow.

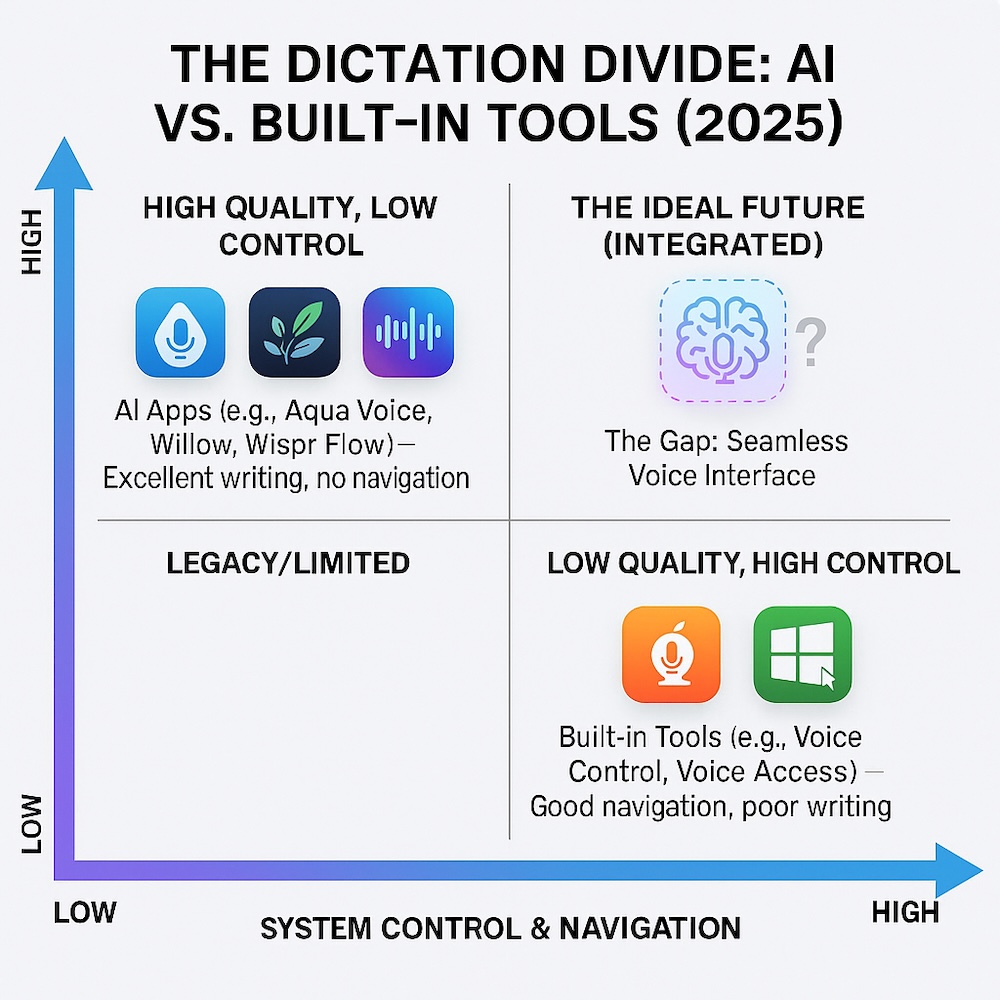

The AI dictation gap: a visual look

AI dictation apps sit in the quadrant with high-quality writing but almost no navigation, while built-in tools like Voice Control and Voice Access offer navigation but poor dictation. The top-right quadrant — where both strengths meet — is still empty.

Why the gap exists — and why it’s no longer defensible

There are understandable reasons why built-in dictation has lagged behind AI apps. Apple, in particular, has historically insisted on on-device processing for privacy and latency. Until recently, models simply weren’t powerful enough to offer true contextual understanding within those constraints.

But the technological landscape has shifted — dramatically

Apple already ships a fast, highly accurate speech recognition model to developers. Many developers say it outperforms Apple’s own keyboard dictation and Voice Control. Ironically, this means third-party apps now have access to better speech AI than the one Apple provides to disabled people who depend on first-party tools.

Microsoft has made some early moves too. In September, it released Fluid Dictation, a new feature inside Voice Access on Copilot+ PCs. Fluid Dictation promises to remove filler words automatically, add punctuation as you speak, and generally tidy up spoken language — exactly the direction these tools should be heading.

But it comes with a glaring limitation: it’s restricted to Copilot+ hardware, which shuts out most Windows users, including disabled people who depend on voice for daily work. I haven’t been able to try Fluid Dictation myself, but on paper it appears promising — just not widely enough deployed to shift the landscape.

Early agentic AI is beginning to appear too. Anthropic’s Claude, for example, now offers a “Computer Use” mode that can operate apps, click buttons and navigate interfaces on your behalf. It’s an exciting glimpse of what a unified voice-and-control system might eventually become. But because it relies on taking screenshots to “see” your screen, today it is slow, inconsistent and nowhere near reliable enough for disabled people who depend on timely, deterministic interactions. Claude shows what’s coming — but also highlights how far we still are from a truly integrated voice interface.

The excuses have expired.

The models exist.

The capability exists.

The need has long existed.

What the future should look like

It’s time for platform owners to build voice systems that treat dictation and navigation as one integrated experience.

Imagine being able to say:

• “Delete that”

—and the system knows whether you meant the last word, the last sentence or the messy thought you never finished.

• “Move this over there”

—and it understands which window and where you want it positioned.

• “Fix that paragraph”

—and it rewrites it in the tone you always use.

• “Open Mail and draft a reply to Sarah about the report”

—and it handles the whole interaction in one step.

This isn’t fantasy. The building blocks already exist in the AI models Apple and Microsoft are working with behind the scenes. What’s missing is the willingness to apply them to the parts of the OS disabled people rely on most.

And in the short term, the ask is modest. I’d be happy simply to dictate a message or email with my voice and send it with a single “send this” command — all inside one AI dictation app, without jumping between systems.

Conclusion: the accessibility revolution that didn’t quite arrive

After a year living almost entirely through voice, I’ve seen both sides of the dictation divide. AI tools like Willow, Wispr Flow and Aqua Voice have shown what’s possible when dictation becomes intelligent. They’ve turned speech into writing with a fidelity and speed that finally feels modern.

But the operating systems we all depend on haven’t caught up. The navigation tools are still valuable, even essential, but the dictation engines inside them belong to another era.

The next step is obvious: merge the accuracy of AI dictation with the deep system control of first-party accessibility tools.

Disabled people shouldn’t have to assemble their own workflows to achieve basic digital independence. The technology is here. The models are here. The need is here. What’s missing is the integration.

If 2025 was the year voice got clever, 2026 should be the year it becomes whole.