Meta is reportedly developing a smart fitness watch, internally codenamed Malibu 2. At first glance, this may sound like just another entrant into an already crowded wearable market dominated by Apple, Samsung, and Garmin. Fitness tracking, heart rate monitoring, notifications — these are well-established features.

But Malibu 2 could represent something far more significant.

If Meta integrates its emerging neural interface technology into a smartwatch, it could solve one of the most fundamental accessibility failures in modern wearable devices.

For many severely disabled people, today’s smartwatches are not accessible at all.

The invisible barrier: wrist raise

The problem is deceptively simple.

Every mainstream smartwatch relies on physical gesture. To wake the screen, interact with notifications, check health metrics, or activate a voice assistant, users must raise or move their wrist in a deliberate and controlled way.

This assumption excludes a large group of people.

Those living with muscular dystrophy, spinal cord injury, motor neurone disease, or other neuromuscular conditions often cannot perform this movement reliably — or at all.

I demonstrated this exact problem in a video eight years ago. The limitation was clear then, and remarkably, it remains unchanged today.

Despite major advances in smartwatch hardware and software, raising the wrist is still required to reliably wake the device and access its assistant. The core interaction model has not evolved.

In 2024, I wrote for The Register about this exact issue. The Apple Watch, despite its advanced accessibility features, remains fundamentally inaccessible to many severely disabled people because of its reliance on physical interaction.

The limitation is not the intelligence of the device. It is the interaction model.

The assistant may be powerful, but if you cannot wake it, you cannot use it.

Meta’s neural interface offers a different path

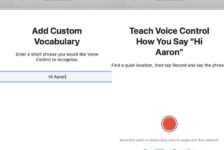

Over the past few months, I have had the opportunity to engage directly with Meta’s accessibility and wearable teams. I also saw demonstrations of the Meta Neural Band — a wrist-worn device that uses electromyography (EMG) to detect electrical signals generated by muscle activity.

This technology does something remarkable.

It can detect intent at the wrist even when there is little or no visible movement.

Instead of relying on physical gesture, it reads the electrical signals that occur when the brain sends commands to muscles. These signals can then be translated into digital actions.

In practice, this means interaction without movement.

Not reduced movement. Not adapted movement.

No movement required at all.

Research focused specifically on severely disabled people

Meta is not developing this technology in isolation. The company is collaborating with researchers at the University of Utah to explore how EMG wrist-based interfaces can improve access to technology for severely disabled people.

The goal is clear: enable people with extremely limited mobility to control digital devices through neural intent rather than physical gesture.

This is not theoretical research. It is practical accessibility engineering aimed at solving real-world barriers.

It represents a shift in how technology can be controlled.

From gesture

to signal

to intent.

Why Malibu 2 could be different from every smartwatch before it

If Malibu incorporates EMG technology — and press rumours say it might — the implications are profound.

The most significant accessibility barrier in wearable technology could disappear.

No wrist raise.

No precise gesture.

No physical acrobatics.

Just intent.

Combined with Meta’s display glasses, this could create a fully integrated wearable ecosystem where users can:

- Access assistants instantly

- Control devices naturally

- Receive and respond to information seamlessly

For severely disabled people, this is not a convenience feature.

It is independence.

Accessibility innovation benefits everyone

History shows that accessibility innovations rarely remain niche.

Voice control, predictive text, and speech recognition all began as assistive technologies. Today, they are used by billions of people.

Neural input could follow the same path.

By removing physical barriers, technology becomes simpler, faster, and more intuitive for everyone.

The best accessibility solutions do not feel like accessibility features. They feel like progress.

A potential turning point for wearable computing

If Meta’s Malibu 2 smartwatch delivers neural input integration, it could mark a genuine turning point.

Not because it adds another fitness tracker to the market, but because it changes how wearables are controlled.

For severely disabled people, this could transform smartwatches from inaccessible devices into practical, independent tools.

For the industry, it could signal the beginning of a new interaction model — one where technology responds to intent rather than physical movement.

Conclusion: watching closely

Malibu 2 remains a rumour for now. But Meta’s investment in EMG research, its collaboration with the University of Utah, and its growing wearable ecosystem point to a clear direction.

This is not simply about launching another smartwatch. It is about removing a barrier that has existed since wearables first emerged.

If Meta succeeds, Malibu 2 may be remembered not as a new product, but as the moment wearable technology became truly accessible.

I will be watching closely — because this time, the underlying technology suggests something fundamentally different.