Meta brought the future to my doorstep

Two weeks ago, something quite extraordinary happened. Meta Reality Labs visited my London home to let me try the new Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses — the first model with a built-in display — bundled with the Meta Neural Band wristband. Officially released in the US on 30 September 2025, and priced from $799, the devices aren’t yet available in the UK— so having them brought directly to me felt both a privilege and an honour.

I live with a muscle-wasting condition called muscular dystrophy, which means I have very limited movement in my fingers, wrists, and arms. Everyday interactions most people take for granted — like pressing a button or tapping a touchscreen — can be physically impossible for me. That’s why innovations like the Neural Band are so fascinating: they hold the potential to turn subtle, barely perceptible movements into real control.

Over the past two years, the audio-only Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses have already been transformative for me. Their deeply integrated voice control has allowed me to do things completely hands-free — from taking and sharing my own photos and videos hands-free to staying connected with family and friends. It’s hard to overstate how empowering that’s been. You can read more about that experience in my earlier piece, Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses review. I was therefore eager to see if this new generation, with its neural input, could open up even more possibilities for accessibility.

A wristband that redefines control

The Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses come bundled with the Meta Neural Band, a slim wrist-worn controller that looks a little like a minimalist fitness tracker. There’s no display or health tracking here — it’s purely a high-tech remote designed for the glasses. Inside, flat electrodes sit gently against the skin to detect the tiny electrical signals generated by wrist and finger movements using EMG (electromyography) sensors.

Those signals translate gestures — such as a pinch, thumb swipe, or wrist rotation — into commands that control the display. The band is worn snugly on the dominant wrist, slightly higher than a watch, and fastens magnetically for a secure yet comfortable fit. It’s splash-resistant, charges via a magnetic pin cable, and typically lasts around a day on a single charge.

Previous frustrations with wrist-worn tech

Before trying the Meta Neural Band, I already had plenty of experience — and frustration — with wrist-worn wearable tech. One of the biggest challenges for me with the Apple Watch is that there’s no gesture to wake Siri that I can perform. Unlike the iPhone, the Watch isn’t always listening, which makes it largely unusable for someone in my situation.

From an accessibility perspective, I’ve long hoped that my very limited muscle signals could one day provide a new kind of control input — something that could respond to the smallest physical effort from people who, like me, can’t produce large movements. That’s why Meta’s work in this area is so compelling.

Testing the Meta Neural Band

To navigate the Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses, you rely on the Neural Band. When I watched Mark Zuckerberg demonstrate the subtle finger movements used to control the glasses at the Display glasses launch at Meta Connect in September, I was fascinated — and hopeful that I might be able to do the same with the limited finger movement I still have.

During the session, I wore the band and tried gestures using what movement remains in my fingers and wrist. It was challenging, but also incredibly moving. A neuroscientist (formerly of Oxford University) now working for Meta fitted and adjusted the wristband while several of his colleagues in the USA followed remotely via Zoom. I really was the guinea pig — but in the best possible way.

Unfortunately, it quickly became clear that I couldn’t perform the available gestures Meta has programmed into the Display glasses for most people due to my muscle weakness. Even so, I genuinely felt that my feedback was heard, and I’m optimistic about the future of this EMG technology for people like me.

Presumably, the EMG system — as it’s currently calibrated for general use — isn’t yet sensitive enough to detect the extremely faint muscle signals coming from my wrist and fingers. But if Meta can fine-tune this sensitivity for people with very limited movement, it could be life-changing.

My optimism is reinforced by knowing Meta is exploring this field deeply — the company is working with Carnegie Mellon University on similar technology to help people with motor-complete paralysis from spinal cord injuries, which you can see in this video.

I left the session hoping that one day the Neural Band will learn to adapt to individual movement patterns, however small and faint they are. If it can recognise and remember every tiny gesture I’m capable of and map them to real-world actions, I imagine it would feel so seamless that returning to full voice control alone would seem like a step backwards.

Voice control as a reliable fallback

Even though physical gestures wouldn’t work for me, I was relieved to see that voice control remains a strong option on the Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses. It meant that even without being able to make physical gestures work with the Neural Band, I could still use my voice to interact with the glasses and get things done — something that instantly made the experience feel more inclusive.

The glasses respond to the familiar wake phrase “Hey Meta”, followed by a natural command. According to Meta’s documentation, you can say things like:

• “Hey Meta, take a photo.”

• “Hey Meta, record a video.”

• “Hey Meta, call [contact name].”

• “Hey Meta, send a message to [contact name] on WhatsApp.”

• “Hey Meta, use Shazam.”

Voice commands can also open maps, control music, turn on captions, check notifications, or ask the built-in Meta AI assistant questions — all displayed neatly in the small heads-up interface.

Being able to fall back on voice control gave me a sense of autonomy that’s often missing from other wearables. It also highlighted how important multimodal interaction is for accessibility: when one input method doesn’t work, another should always step in to keep the experience seamless and inclusive.

Exploring the Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses

These glasses retain everything the audio-only Ray-Ban Meta models can already do — like hands-free music, calls, messages, and capturing photos or videos — but the addition of a display transforms them completely. You can now see and reply to texts, view Instagram Reels, frame shots in real time, read captions or translations of conversations around you, and get walking directions with a live map floating in your view. When you interact with Meta AI, it presents visual cards and information directly within your line of sight.

I explored some of Meta’s built-in apps, and Maps particularly stood out. I briefly tested navigation — just a few feet across my living room — but it was the first time in my life I’ve ever been able to access navigation independently. Google Maps on a smartphone has always been out of reach for me, so this was a major milestone — right up there with the first time I could take and share a photo myself using the audio-only Meta glasses. I’m already imagining touring parts of London in my wheelchair with navigation quietly guiding me along the way.

Seeing turn-by-turn directions and nearby points of interest appear within my line of sight felt futuristic, but also deeply practical. For disabled people, especially wheelchair users or those with limited mobility, this kind of unobtrusive visual assistance could be genuinely empowering.

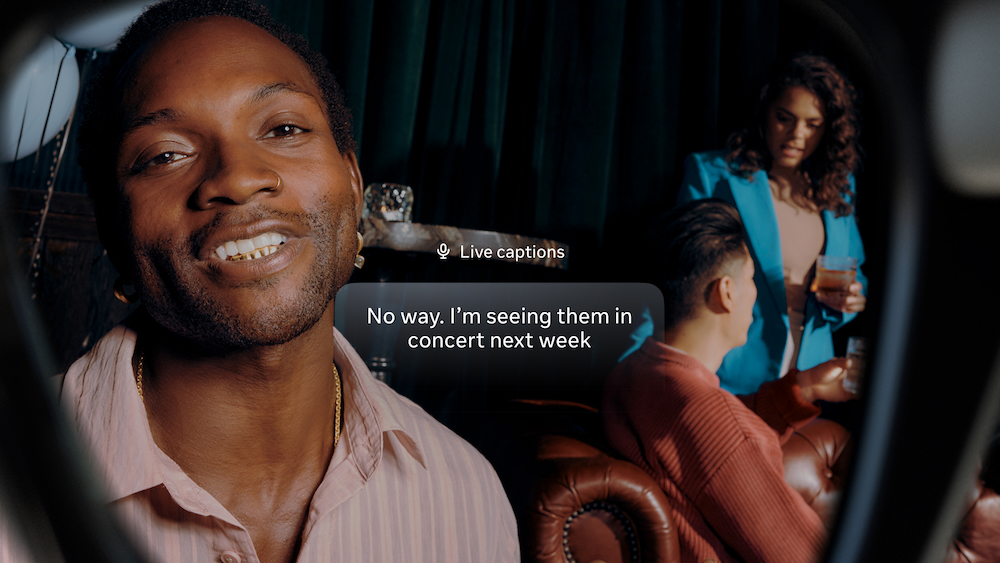

I also appreciated the ability to adjust text size and contrast directly in the display — features that make a huge difference to comfort and readability for many people. And the live captions feature, which transcribes spoken words in real time, has enormous potential — not just for deaf and hard-of-hearing people, but for anyone who benefits from having information displayed visually in noisy or distracting environments.

Thoughts on the Display glasses

This isn’t a review of the Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses themselves — my time with them was fairly short — but they felt light and comfortable, not unlike the audio-only Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses I wear daily. The built-in heads-up display is crisp, subtle, and cleverly positioned so it doesn’t dominate your view. The software still feels early, but the foundation is solid.

While I couldn’t yet make the gestures work with my level of movement, the session left me more excited than ever about what’s possible once accessibility is built in from the start. If Meta can make gesture input accessible to someone like me, they’ll make it easier and more intuitive for everyone. Accessibility drives innovation — not the other way around.

A privilege to take part

Moments like this remind me why accessibility in technology matters. It’s not just about convenience or novelty — it’s about independence, dignity, and the human need to participate fully in life.

To have Meta bring unreleased-in-the-UK technology halfway across the world and let me test it in my home was humbling. It showed a genuine willingness to learn from lived experience and to involve disabled people in the design process — where inclusion matters most.

What impressed me most was the attitude of the Meta team. They weren’t there to sell or show off — they were there to learn, to understand how this technology could evolve to include people with a wide range of abilities. I talked about how solving accessibility challenges often leads to better design for everyone.

I came away from the demo hopeful. This wasn’t just about smart glasses or neural sensors. Trying the Neural Band felt like the start of a new conversation — one that could eventually make technology more responsive to human ability than ever before.

Takeaway

Technology is most powerful when it adapts to people, not the other way around. Meta’s work with the Neural Band and Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses hints at a future where control is more intuitive, personal, and inclusive — and where accessibility shapes the next era of human–smart-glasses interaction.

For example, being able to summon the Meta assistant with a subtle gesture would be huge — the assistant is the gateway to so much of my independence.

My challenge to Meta now is to take that vision further — to build gestures that people like me, and others with spinal injuries, motor neurone disease, or the effects of a stroke, can perform. It would be fantastic to see gestures introduced for everyday actions like waking the assistant, hanging up a call, or capturing a photo or video. The goal should be to make the glasses controllable through the smallest possible movements of the fingers or wrist.

Looking ahead, the ability to trigger connected smart-home routines — say, opening my electric front door — with a single gesture would be genuinely life-changing. After all, no one wants to shout ‘open the door’ through their earbuds or glasses across the street; a discreet twitch of a finger would be a far more elegant solution.

Meta’s aim with these glasses is to let people keep their phone in their pocket — to act without pulling it out. I can’t easily pick up or use a smartphone, so for me, the Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses feel almost as if they were made for me.