Among Meta’s many announcements at CES 2026, one stood out for me — not because it represents a finished product, but because it represents a research direction I have been advocating for in my writing for a long time.

Meta revealed early-stage research with the University of Utah exploring how EMG (electromyography) gestures with its Meta Neural Band could one day be used to control smart home devices. As someone living with muscular dystrophy, I am thrilled to see that people with neuromuscular conditions — including those with ALS and other motor-impairing disabilities — are a central focus of this research.

While EMG interaction via the Meta Neural Band is now reaching early adopters, the shift toward using it for environmental control (rather than just navigating a screen) is the piece of the puzzle I’ve been waiting for.

For those of us who rely on technology to interact with our home environment, research like this is where meaningful change actually begins.

Why EMG matters

EMG works by sensing electrical signals generated by muscle activity at the wrist. Unlike touchscreens or voice commands, EMG gestures can be subtle, personal, and adaptable — allowing interaction without needing fine motor control, physical switches, or constant speech.

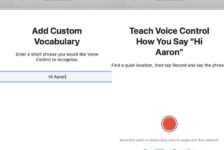

This is not “hands-free” technology. EMG is about using your hands differently, in a way that can be tailored to an individual’s physical capability. That flexibility is precisely why it holds so much promise for disabled people. Voice control requires speaking aloud (which can be tiring or socially awkward), and touch requires physical accuracy. EMG is “silent” and internal, which reduces the social and mental friction of controlling a home.

Meta’s research aims to explore how simple, custom EMG gestures could eventually be mapped to smart home actions — such as controlling blinds, locks, thermostats, and more. For many disabled people, these are not conveniences; they are fundamental building blocks of independence.

Why this research matters now

I’ve been talking for a long time about the need for direct, reliable smart home control that does not depend solely on voice or touch. Both have their place, but both also break down — sometimes unpredictably — in real-world use.

Before Christmas, I took part in a demo involving Meta’s Display glasses and EMG input with the Meta Neural Band. What struck me wasn’t polish or readiness, but potential. Even in an early form, it was clear that EMG with the Meta Neural Band could offer a more intentional and controllable way to interact with technology — one that feels less like issuing commands and more like direct interaction.

This research with the University of Utah feels like a continuation of that idea, taken seriously and explored in partnership with academic experts. Critically, the university will be using the neural band to explore control options for the TetraSki—an alpine ski designed for people with complex physical disabilities. Currently, the TetraSki relies on joysticks or “sip-and-puff” mouth controls. By testing if a EMG wristband can handle the high-stakes precision needed to steer down a mountain, the team is performing the ultimate “stress test” for the hardware. If the technology is reliable enough to navigate a ski slope, it is far more likely to be reliable enough for the critical tasks of daily living at home.

CES 2026: the wider picture

The EMG smart home research sits alongside several other Meta announcements at CES 2026. These include:

- EMG-based handwriting: Research into high-fidelity text input via wrist-based signals.

- Teleprompter-style features: A new display glasses feature that could be a significant accessibility tool for neurodivergent users or those with speech and memory difficulties

- Wearable input experimentation: Broader research into how we interact with technology across different environments.

Meta also confirmed that the rollout of its Meta Ray-Ban Display glasses has been paused outside the US, including in the UK, due to limited initial availability.

Taken together, these announcements paint a picture of a company investing in long-term interaction research, rather than short-term product cycles.

A cautious but hopeful step

None of this research guarantees outcomes. EMG-based smart home control for disabled people may take years to mature, and many challenges remain — technical, practical, and ethical.

But what matters is that this work is happening at all, and that it is being framed around real needs rather than abstract use cases. By testing these systems in rugged, real-world scenarios through the University of Utah, there is a better chance the eventual technology will be reliable enough for daily life.

For me, the idea that one day I might reliably control my front door through EMG is not about novelty. It’s about autonomy, and not having to fight technology that was never designed with people like me in mind.

This is early research. But it’s the right kind of research — and it’s encouraging to see it finally being explored.