Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses have been life-transforming for me and for many others with severe physical disabilities. As the company’s smart glasses, they already show how powerful voice-first, wearable technology can be by removing the need to reach for a phone, press buttons, or interact physically with hardware.

For me, that’s already meant being able to take my own photos and videos hands-free, using my voice alone. No phone to hold, no shutter button to press, no need to ask someone else. It’s a small interaction, but a deeply liberating one, and a clear example of what voice-first technology can make possible when physical barriers are removed.

That level of independence already exists in the product itself, which is precisely why the limitations of the Meta AI app matter so much.

An Accessibility section that doesn’t reflect the product

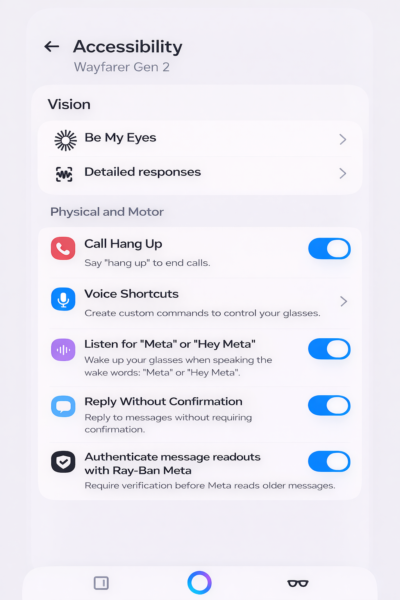

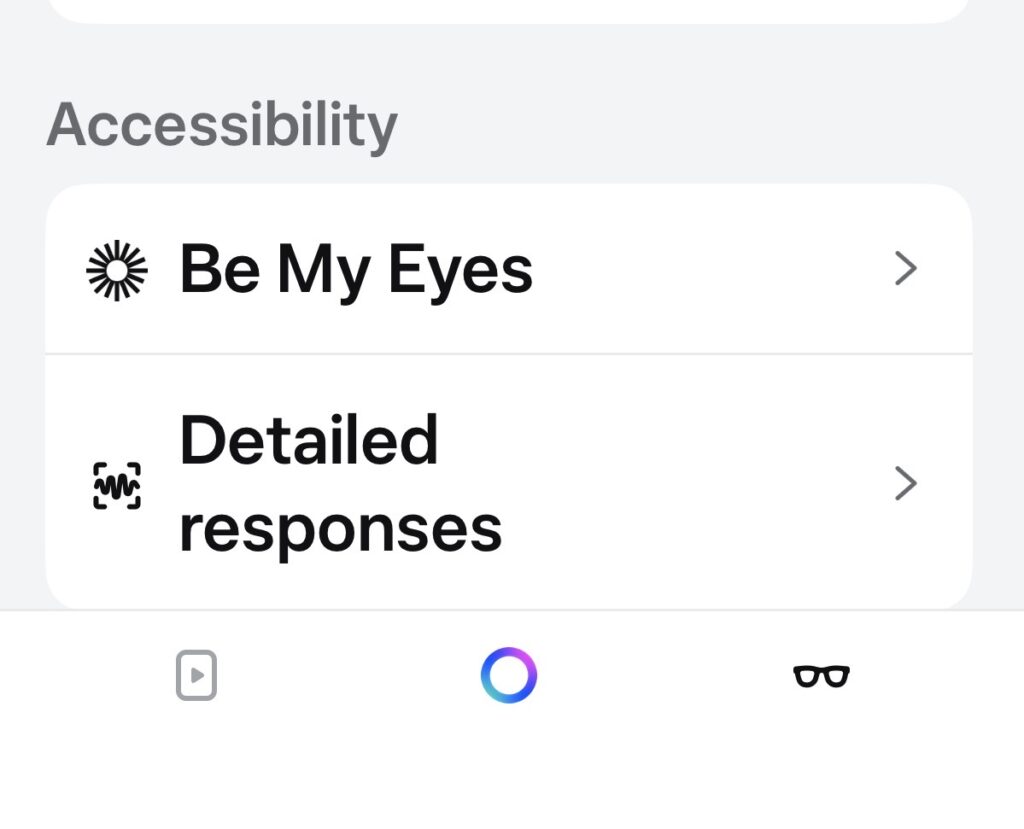

Open the Accessibility section in the Meta AI app and you’ll find features focused almost entirely on vision. Tools such as Be My Eyes and detailed responses are valuable and important.

No settings that recognise limited strength, fatigue, breath control, dexterity, or the reality that tapping, swiping, or confirming actions on a phone or the glasses may be difficult or impossible. As a result, many everyday interactions quietly push users back to the phone. That undermines the very independence the smart glasses are designed to enable.

Physical accessibility is rarely about one dramatic barrier. It’s about repeated, avoidable friction.

Why physical and motor access needs its own section

Physical and motor disabilities create interaction challenges that are fundamentally different from vision or hearing needs. They often involve:

- Difficulty performing precise or repeated physical actions

- Fatigue that makes confirmations and retries exhausting

- Limited breath that makes long voice commands impractical

- Situations where taking out a phone is itself a barrier

When these needs aren’t addressed directly, even voice-first hardware ends up relying on touch-first assumptions.

That’s the gap in the Meta AI app today.

A simple, realistic proposal

The mock-up shared alongside this article proposes a modest but important change: a dedicated “Physical and motor” section within Accessibility, sitting alongside Vision.

Not a redesign. Not experimental features. Just an acknowledgement that physical and motor access deserves first-class treatment.

The proposed settings include:

- Call hang up

Reliably end calls using voice alone — for example, “Hey Meta, hang up.” No buttons, and a straightforward way to deal with spam calls. - Voice shortcuts

Custom commands that reduce the need for long phrases, helping people who experience fatigue or limited breath. It’s worth noting that Meta already understands the value of shorter, task-specific voice commands. Variants of voice shortcuts exist in Meta’s athlete-focused Vanguard smart glasses, where they’re positioned as a way to reduce effort and speed up interaction during activity. The same principle applies — even more strongly — to accessibility. What helps an athlete in motion can be essential for a disabled person managing fatigue, breath, or limited strength. Voice shortcuts shouldn’t be a specialist feature; they should be a core accessibility setting. - Listen for “Meta” or “Hey Meta”Shortened wake-word options that reduce vocal strain and effort.

- Reply without confirmation

Fewer unnecessary prompts when messaging, supporting faster, more autonomous interaction. - Authenticate message readouts with Ray-Ban Meta. Securely allow Meta to read out older or missed messages on request — without needing to take out a phone — similar in spirit to “Authenticate with Siri”.

None of these ideas are radical. All are technically feasible. Several already exist in other ecosystems.

This has been done before — and it works

Over the years, I’ve publicly called on Apple to take voice-first interaction seriously across its devices. In 2020, I set this out in The Register, arguing that voice needed to be treated as a core input method for people who cannot reliably use touch. Apple did respond , and many of the capabilities that followed have since become essential to how disabled people use iPhones and other Apple devices.

The lesson is consistent: when physical and motor access is treated as a first-class concern, usability improves not just for disabled people, but for everyone — including those dealing with injury, illness, fatigue, or situational limitations.

Accessibility should not stop at one disability group

Inclusive design works best when it recognises that accessibility is not a single category. Vision, hearing, cognitive, physical, and motor needs all deserve equal consideration.

Meta has already built something powerful with its smart glasses. The foundations are there. Expanding the Meta AI app’s Accessibility section to include physical and motor disability needs would be a natural and overdue next step.

Not as a concession, but as good product design.

I’d welcome a conversation with Meta’s product and accessibility teams about how a Physical and motor section could be explored and developed in future updates.

What accessibility features would you like to see in the Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses? Let us know in the comments below.